Killing Time at Lightspeed and the Ordinary Horror of Losing Touch

You are hurtling away from Mars aboard a vessel traveling at the speed of light; a journey of 29 years experienced in less than an hour. Behind you are your friends, family, the life you once lived. You seek something better at the far end of the galaxy, a fresh start in a new world. But still, you cling to pieces of your former life like a raft in the infinite void. You turn on your phone to check FriendPage, but with each refresh, years roll by for those you left behind. You are left to fill in the blanks as news travels slow, painfully slow, and you witness the lives of those you left behind as an in-flight movie, watching from afar more disconnected than ever. ///

It is bizarre to think that Facebook launched in 2004. Only a little more than a decade ago the idea of “liking” your friend’s post, of being able to instantly look up nearly anyone in the world, and having the ability to befriend both close friends and complete strangers with the press of a button would have seemed incredibly alien.

Now, social media is among, if not the biggest entity in our modern world. With constant connectivity comes a constant dialogue, one which has entirely shifted both how we see other people and how we think about interactions with them both online and off. To ignore social media is to effectively render yourself obsolete in the eyes of many, and to use the service casually is to invite scorn for missed updates and important events. Social media at this point is simply culture, a space more habitually inhabited than common rooms and parks, assembled from the varied interests of all its users in a distressing trash heap of enthusiasm and disgust.

There has been a lot of talk over the last year as to the ways social media creates bubbles around us, forming echo chambers for us to shout in while the conversation goes nowhere. I’ve been thinking about this a lot as I scroll through my feed every day, getting lost in a sea of memes and political outrage. I’ve begun to wonder about the conversations that’s are not being had, the people who are no longer talking, and what I’m potentially missing by sitting here refreshing a page instead of making plans with my friends or going outside. These thoughts wash over me in a haze, and suddenly I feel old and tired, unable to relate to what I’m seeing and feeling exhausted by the effort needed to break through someone’s digital façade to see the person underneath. Inevitably, I refresh the page and hope for something better.

It is an intensely lonely experience, to be both a part of someone’s life and yet have such a small role in it

///

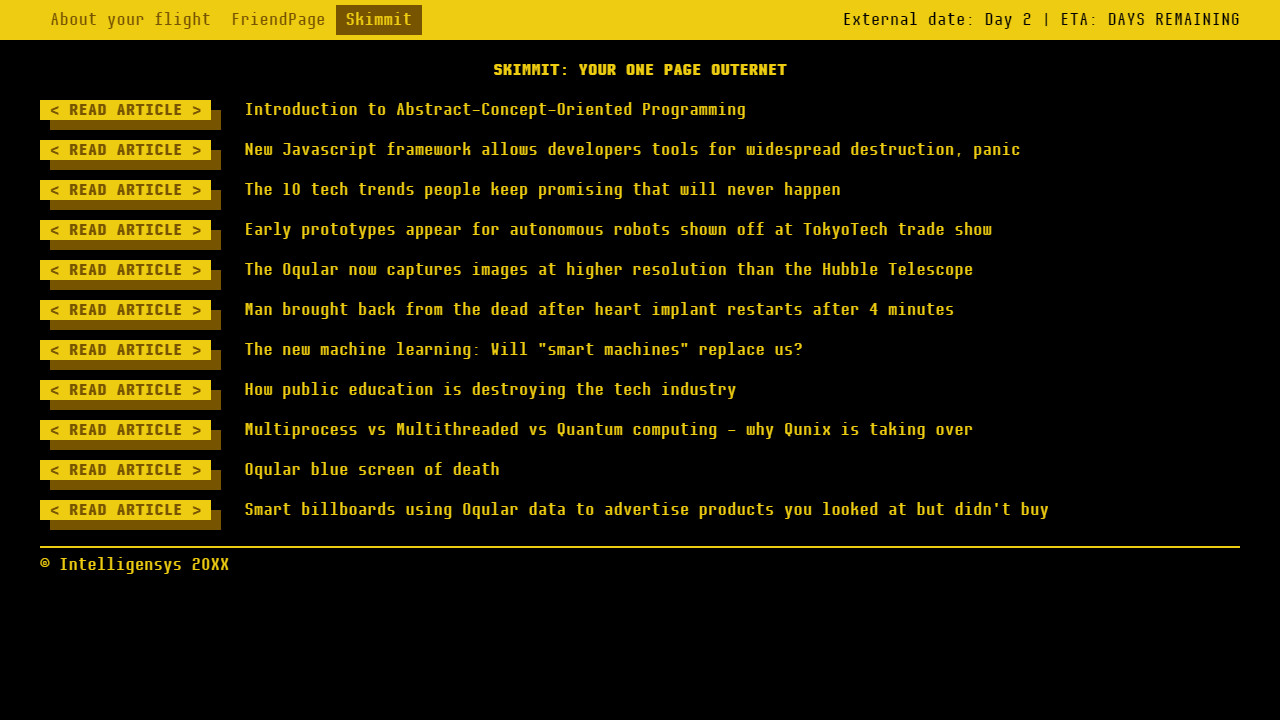

Killing Time at Lightspeed (2016) is ostensibly a game about social media, but in truth, it’s a game about losing touch with the people you care about. Aboard the SpaceY ISST Kelvin, you are presented with a social network wherein information is sent and received with a year or longer delay, allowing you to send and receive messages as well as read through news posts and status updates, but experiencing it all in bits and pieces with indeterminable gaps in between.

You may read that your friends are in a relationship, only to refresh the page to find they are no longer speaking to each other. The news feed details contemporary social issues giving rise to civil unrest and political overreach, but out among the stars you catch only the headlines and significant events, watching complex moments in history from a voyeuristic distance only able to “commend” posts and occasionally interject with a comment that will have long since lost relevance by the time it reaches home.

It is an intensely lonely experience, to be both a part of someone’s life and yet have such a small role in it that you are little more than a fly on the wall. Killing Time at Lightspeed, in many ways, feels like a meditation on the distance that forms between us when all our interactions take place behind screens. Watching someone grow and change and find love begins to feel empty and foreign when their life is distilled into notable events and status updates. Our lives are more than can be said in 140 characters, but that hasn’t stopped us from trying to do so.

///

This past year my grandmother died. I learned of it via a text from my mother, something along the lines of “I thought you ought to know.” I wanted to feel sad, upset that I hadn’t visited her in so long, any emotion that would do justice to the life and death of such an incredible woman. But all I could think about was that text. It’s cold, blunt simplicity, just words on the screen no different from a shopping list or an ETA. Later my sister posted a brief eulogy and picture of my grandmother on Facebook, and the most I could think to do was “like” her post. I felt sick and put my phone away.

///

Around halfway through Killing Time at Lightspeed one of the characters stops logging into FriendPage. She’s not dead, I’m informed by a mutual friend, she just needed to get away from the internet. In game I commented that I thought it was good for her to spend some time offline, but in reality, I was beginning to tear up that she would suddenly cease to exist insofar as I could contact her. Suddenly I began to wonder what our friendship really meant. How do you judge a relationship continued solely through intermittent texts from someone you know you will almost certainly never see again? Are you still friends if they stop logging in? Is a rejection of the social network, in turn, a rejection of you?

If suddenly everyone stopped using Facebook, would we still be friends with the hundreds of faces that make up our friendslist?

Killing Time at Lightspeed does not posit any easy answers as to what the role of social media in our lives means, or whether relationships made possible with 1s and 0s are any less valid than those made face-to-face. The game does not propose to reject social media on principle, but nor does it treat it simply as a necessary evil. Like our own relationship to technology and constant connectivity, Killing Time at Lightspeed’s approach to social media is complicated and messy. Its vision of the future is not an abstract impossible concept, but a reality we edge closer towards by the day.

At its core, Killing Time at Lightspeed seeks to examine what it means to be connected to someone. How we tend to take social media and the people who use it for granted, and how our relationships would change if suddenly everyone stopped using Facebook. Would we still be friends with the hundreds of faces that make up our friendslist? Would we care enough to find other ways to connect when we can no longer scroll through a summary of life events and offer our empty approval? Or would we all simply drift apart, as if all those likes and comments really didn’t mean anything after all?