Call of Juarez: Gunslinger, or "The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly Sides of a Modern Shooter"

There is a scene early on in Gore Verbinski’s 2011 animated western, Rango, in which Johnny Depp’s titular chameleon is attempting to endear himself to the townsfolk after bumbling his way into town. Through a display of increasingly frantic and outrageous dramatics, he weaves a fantastic tale of his fight with a band of notorious outlaws, an account which the townsfolk have completely bought into by the end despite being fabricated on the spot and held together with the thinnest of logic. Though the scene’s primary purpose is to position Rango as a respected member of the town, as well as to play off his insecurities and reliance of acting in all his social encounters, it also feeds into one of the most persistent and engaging tenants of spaghetti westerns: a stranger’s tale told over a glass of whisky at the town saloon. Storytelling is among the most fundamental aspects of human socialization, but it has a special position within the narrative of the wild west. Given the sparseness of towns sprinkled across seemingly endless plains, and the lack of any form of correspondence faster than a letter, information was in short supply. A newcomer became then not only a curiosity but a window into life outside a given town, as much a source of news as entertainment. The stories may sound absurd, but who is to say they aren’t true when the only one able to vouch for their legitimacy is the storyteller herself?

It was this idea, and the before-mentioned scene from Rango, that kept running through my mind as I made my way through Call of Juarez: Gunslinger, a bite-sized offshoot of a series whose continued existence after the abhorrent The Cartel is as surprising as the direction developer Techland has taken it in. Far more than any of the three games that preceded it, Gunslinger is enraptured with the spaghetti western in its campiest, most iconic incarnation. Setup as a barside retelling of famed bounty hunter Silas Greaves’ exploits, Gunslinger is a hodgepodge amalgamation of western iconography, shooter conventions, and game design tomfoolery.

Train heists, bank robberies, standoff duals, and a lifelong quest for revenge, Gunslinger indulges itself on every western trope known to the genre, framing it all around Greave’s increasingly ridiculous encounters with famous outlaws. Greave’s constant narration of his adventures is one of Gunslinger’s most successful hooks, his charismatic narcissism and increasingly unreliable nature providing the otherwise soulless shootouts with a sense of character. His repeated backpedaling of events to say “what really happened” borrows a page from Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time in allowing the game to organically account for inconsistencies (read: your death), as well as put you into impossible scenarios that break the narrative but are no less fun to play through.

Unfortunately, this conceit grows tiresome after a few hours, once it becomes clear that the narrative is little more than a stream of consciousness excuse to shuffle you from setpiece to setpiece like an incoherent theme park ride. Gunslinger tries to mask its meandering pacing by pitting the player against an onslaught of different outlaws, each with their own story of dubious authenticity, but the result is like a greatest hits album for a band without enough songs to warrant one. A few of the outlaws lend themselves well to Gunslinger’s shooting gallery design, but most feel interchangeable to one another, as cookie cutter in their personality as the levels that surround them. It doesn’t matter much if the Gatling-gun is on a hill or in a cave, or if you have to hold off an ambush from inside a house or inside a barn, all that has changed is the shifting of assets and the alteration of a few lines of dialogue (how many “fastest hands in the west” can there really be, after all?).

But the repetition is as much the fault of the narrative, as it is the familiar gunplay. Gunslinger is basically an assemblage of neat ideas from more inspired games. Bastion’s narration is adjoined to Bulletstorm’s storing system, outfitted with Max Payne’s slow-mo shooting ability, and blended together with Borderland’s art style and enemy AI. The concoction is, admittedly, wildly successful at what it tries to do. Guns are disinteresting in their design, but with only three to choose from, it’s easy enough to find what works for you and ignore the rest. Enemies are mindless, but it’s enjoyable enough to watch points pop out of them. Concentration (which slows down time and highlights enemies) may feel a bit like cheating, but Gunslinger exists for no other purpose than to make you feel like an invincible, well, gunslinger, so have at it!

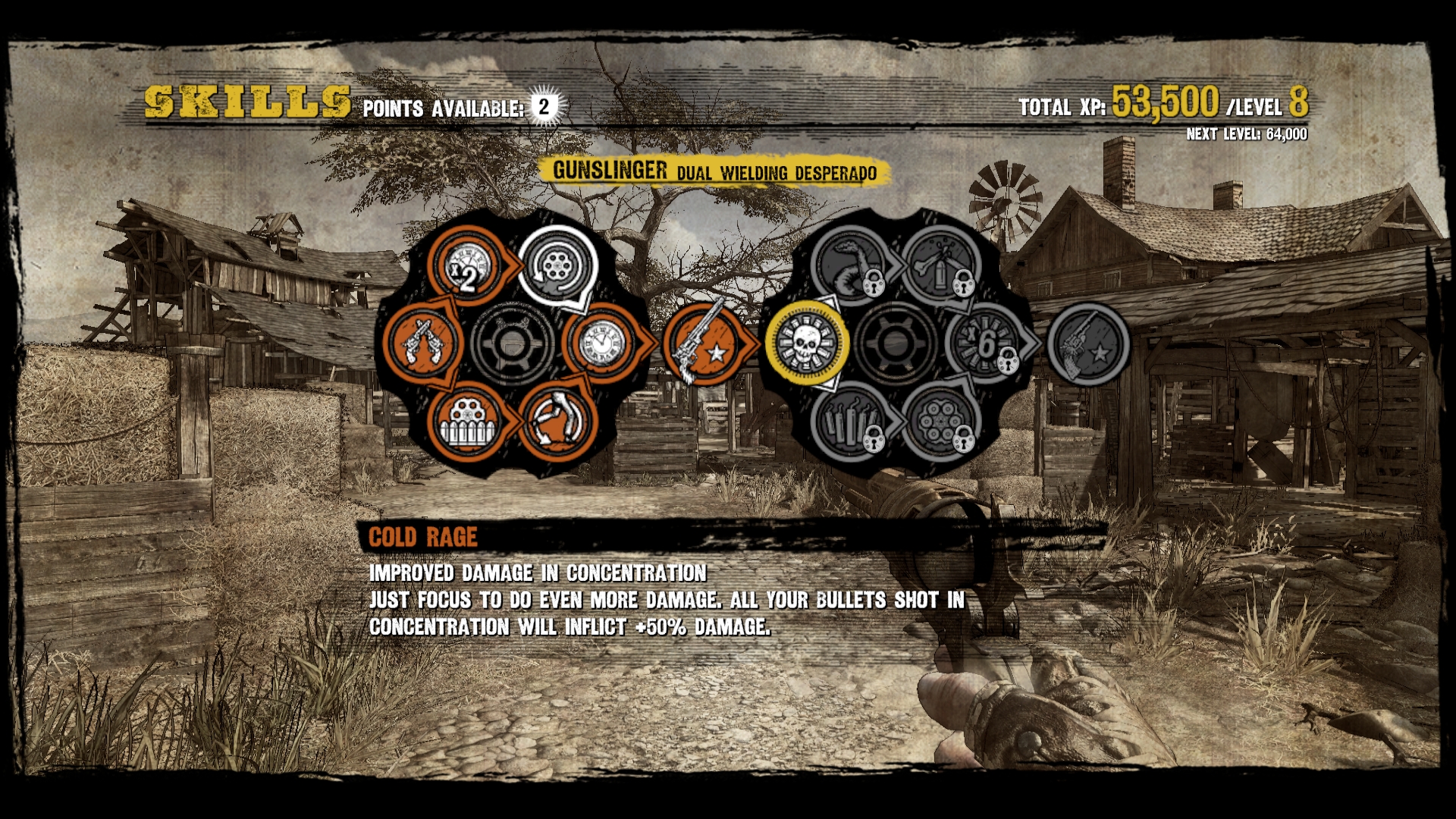

Gunslinger is perfectly ridiculous and unremarkable, but it sells itself well enough that it’s easy to buy into its Frankensteinian collage of games and just enjoy the dumb ride. For a time. Like its narrative, Gunslinger’s gunplay begins to feel route and tedious a few hours into its already short runtime of about 4-5 hours. Fights take longer and longer, and death becomes a more contentious presence. An upgrade tree tries to remedy Gunslinger’s repetition, but its additions are more a matter of convention than interesting perks. You might need a larger ammo clip because you’re facing more enemies at once, but nothing changes about the shooting on a fundamental level, and the few cool ideas Gunslinger has along its upgrade path remain little more than quality of life improvements than mechanical game changers.

Surprisingly, Gunslinger proves significantly more enjoyable as a shooter when most of its extraneous components are stripped away in its arcade mode, which effectively transforms the game into a lightgun shooter ala-Time Crisis or the on foot levels of Rebel Assault II. By shifting the purpose of earning points off of uninteresting level gains and over onto leaderboard chasing, Gunslinger’s combo and skill shot features begin to actually matter. Arcade mode also cuts out almost all the traversal downtime of the main game, populating levels with more enemies that pop out like animatronic tin targets, and tweaking the gunplay to be just a little more forgiving (which is for the best, as Gunslinger is about looking cool and shooting fast, not reveling in precision). None of the maps quite stand out enough to create a heated leaderboard showdown, but arcade mode still serves as a nice palate cleanser to the comparatively mundane shooting of the single player game.

Gunslinger is about looking cool and shooting fast

It deserves to be said that even if Gunslinger is only a decent shooter with an underutilized setting, coming after The Cartel – a game so bad its CEO denounced it as a mistake – this is more than I would have ordinarily begun to hope for. But like a rash that refuses to go away, Gunslinger can’t seem to shake the most troubling issue that has plagued the series to varying degrees since it’s incarnation: minority representation. Though it may be nowhere near the abhorrent mess that was The Cartel’s take on human trafficking, Gunslinger’s portrayal of Native Americans can barely sneak past as less than straight up propaganda. Whether or not it is appropriate for the setting is irrelevant; headshotting Native Americans as a white man in a decidedly dumb first person shooter is, and probably always will be, in incredibly poor taste.

Gunslinger goes a step further though by attempting to justify the inclusion of a level which is as irrelevant and meaningless to the overall plot as any other. As you are gunning down dozens of Apache warriors, Greave’s expresses that he had “some doubts” about his actions, and that he understood the pain the Apache felt (their “crime” being that they retaliated against the US army after they mascaraed their tribe during a ritual). After this, the level goes on unhindered, but that Techland seemingly recognized their mistake, acknowledged it in game, but then decided to go forward with it anyway, makes it even more disgusting. They want to have their gross cake and eat it too, but all it accomplished was nearly causing me to drop the game in outrage.

Final Word

Gunslinger is a fine shooter that endears itself through a love of its setting and an unconventional approach toward narration and how it can inform game design. Its hooks begin to slip sometime before its conclusion, but Gunslinger is so easy to engage with that it never becomes unpleasant even as it grows a bit stale. Its depiction of Native Americans is horrendous, and prevalent sexist and racial slurs regrettable, but at the very least Gunslinger makes some headway in distancing itself from its train wreck of a predecessor. Gunslinger isn’t a great game, but it’s the one that does the best to make a case that Call of Juarez can be more than a western pastiche filled with racial grievances, if only to a point.