Silent Hill, Rule of Rose, and the aesthetics of nightmares

There’s a moment towards the end of Rule of Rose (Punchline, 2006) where I got what it was doing. A room that I needed to enter was blocked by four thin strips of paper, each requiring a different item to remove. It’s a silly way of framing a pretty standard lock and key puzzle and that’s entirely the point. This relatively innocuous challenge makes material the feeling of having progress blocked by something that, realistically, is easily surmountable.

It's common to say that a horror game feels like a nightmare. They often contain things we associate with bad dreams: monsters, dark rooms, and disorienting audiovisual design. However, it's rare that I see a horror game truly capture the subtler aspects of nightmares, such as actual helplessness, stagnation, an inability to move forward, or to move on. The paper over that door couldn't be crossed because Jennifer's mind wouldn't let her,and this modality is present in just about every aspect of the game's design. When they're more obtrusive and less contextualized, these level design choices can sap a game of its verisimilitude (ala, the frequent employment of invisible walls). Rule of Rose, however, lives deep within unreality and makes that known to the player by rejecting physical logic, embracing a freedom with its levels not afforded to many similar games.

Rule of Rose follows Jennifer, a 19 year old girl returning to an orphanage where she spent some time early in her life. Structurally, it’s a series of vignettes, each taking the form of a children’s story that’s been bent out of shape. At the beginning of each chapter, the player is given a small scrap of a picture book to read, which always has a disturbing or cruel resolution. The level that follows sees Jennifer going through the motions of that story, towards its disastrous conclusion that you and she both know is coming. At its core, the game is about abuse, and how abuse colors the way we see the world. Very little that happens in the game is “real” as the player experiences it, but rather a fantasy built from memories stacked on top of each other and contorted into something recognizable but heightened and disjointed. What we’re playing is not literal, but rather represents what a given experience felt like, as opposed to cleanly showing the player what “objectively” happened in Jennifer’s life.

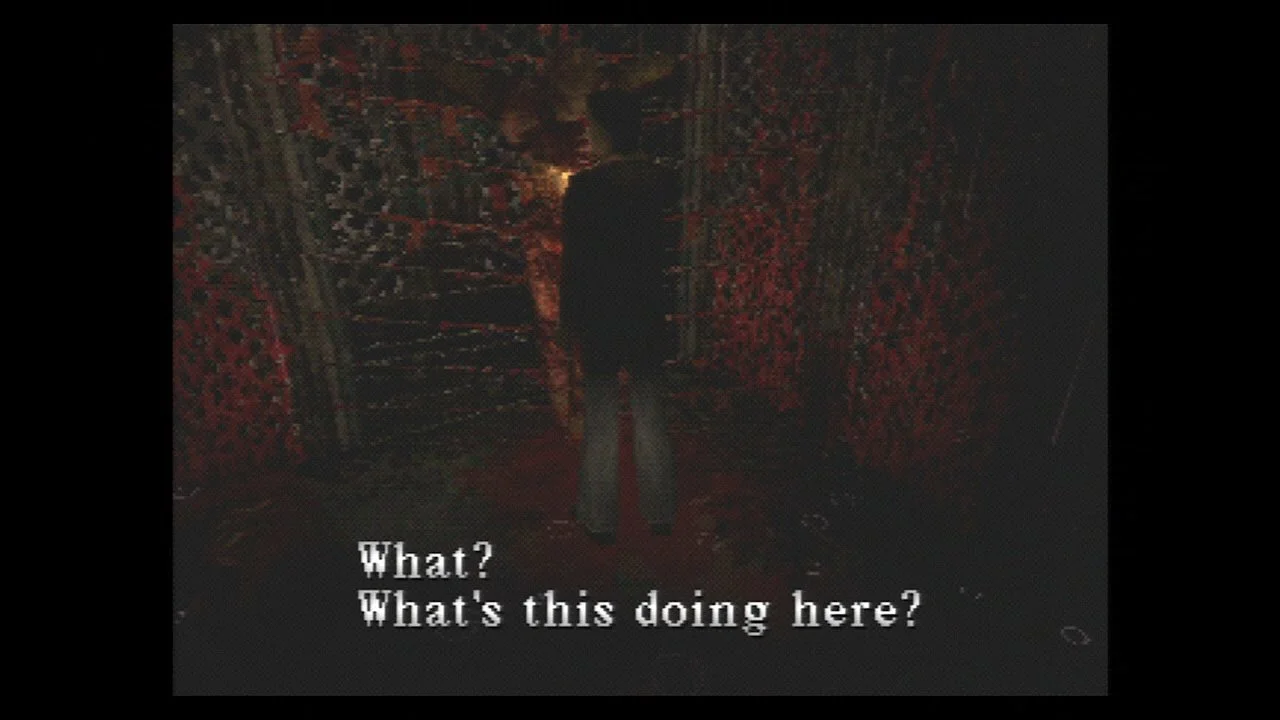

Games like Rule of Rose take many cues from the Silent Hill series, which functionally laid out a blueprint for how to do 3D psychological horror that we're still referencing. Like Rule of Rose, we can learn a lot from how Silent Hill conceptualizes nightmare aesthetics, and how that's made apparent through its level design. The first Silent Hill (Team Silent, 1999) starts with a nightmare, which serves as foreshadowing for some of the awful things to come. Player character Harry is navigating a hallway that grows increasingly dark until he finally pulls his flashlight out, mildly illuminating his surroundings. The walls are rusted and brown-red, made of grating and wrought iron. Harry comes across a body crucified to an I-beam, and as the camera tilts up, voltage runs through the corpse as it begins to violently convulse. When the player regains control of Harry, several small creatures with knives emerge from the darkness and stab him to death, jolting him awake.

Harry encountering a crucified body in Silent Hill.

The atmosphere in this starting segment is important as it introduces the player to Silent Hill's Dark World, or the nightmare space the player will occupy for the back half of the game. When Harry arrives at Silent Hill, he’s greeted with a barren town and many locked doors. It is unusual, but hardly the terrifying town from his dreams. A clear explanation is never given for how or why the town of Harry’s dream became so monstrous and antagonistic, planting a seed of dread that will inevitably emerge.

As with Rule of Rose, Silent Hill plays with using its world to dictate where the player can and cannot go, level design conveying as much narration as the text itself. Run too far east down Finney Street and the road simply ends. There's an insurmountable cliff where part of the town used to be, as if it was swallowed whole by the earth. Standing on this precipice, overlooking Finney Street, the player sees only endless fog extending into nothingness. This image is scarier than most monsters in the game. It's unexplained, barely even remarked upon. Harry accepts the impossible geography because what else can he do? Silent Hill keeps everyone who enters only as long as it wants, before inevitably disposing of them.

This image resonates with me because it's so believable. A similar thing happened in a town near where I grew up, many years ago. The ground caved in, destroying a huge chunk of the infrastructure it was built on. That story continues to chill me. The nothingness at the end of Finney Street, however, works a bit differently. The idea of a town being destroyed by an earthquake or landslide isn't unheard of, but the depth and absoluteness of Silent Hill’s cliff gives it an uncanny edge that is hard to match in real life; hints of dream logic seeping into what we might consider the "waking" version of Silent Hill.

Rule of Rose and Silent Hill operate in uncanniness rather than outright horror, disorienting and offsetting the player. Both have a fair amount of terrifying imagery and scenarios, but the sense of something other creeping into the fundamentally real and familiar is what sets them apart and, paradoxically, makes their horror feel tangible. Freud, in his paper on The Uncanny described it as a "class of frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar." That familiarity is what gives nightmares their power over us. Even though many of us, myself included, often dream of dark forests, monsters, and the end of all things, I'd estimate that most of our bad dreams are far more mundane. Consider a dream where you let down someone you care about, or one where you need (for unknown but still compelling reasons) to get into a room but can't fit the key into the lock. These are the kinds of dreams that Silent Hill and Rule of Rose are referencing, far before the monsters come.

There are traditional monsters in Rule of Rose, but few are as menacing as the other human characters. Aside from Jennifer, the game’s main cast consists entirely of children that the world has been unkind to. They call themselves The Red Crayon Aristocrats, and they’re all too eager to invert the oppressive power structures that they grew up under to strip Jennifer of her agency. They create arbitrary rules that she cannot realistically follow, punishing her for breaking them all the same. They enforce a strict hierarchy, requiring that she only do what they want, without room for deviation.

The Red Crayon Aristocrats in Rule of Rose.

The Red Crayon Aristocrats are deeply complex and broken characters, behaving in ways that are internally consistent but with room for growth and change, if rarely for the better. There is no way to mechanically fight back against their tyranny, even though Jennifer is 19 and should be able to easily overpower and out-wit a group of children. She is meticulously beaten down, her ego annihilated by their malevolence. I find that in my own bad dreams, as well as many of my friends who I’ve talked to whilst writing this piece, a lack of control over my actions is a potent driver of the discomfort I feel. This is systematized by the Red Crayon Aristocrats; they set standards of behavior and action that must be adhered to. A player cannot proceed in the game without doing what they ask, however horrible.

In one chapter, Jennifer is collecting pieces of a note from one of the girls. She spends the entire chapter being led around in circles, each piece of refuse pointing her to another, spiraling into a special kind of cognitive dismay in which progress is perpetually just out of reach. When she finally finds the last piece, Dianna (the self appointed leader of the girls) rips it to pieces. Jennifer is blamed for this and punished by being sealed into a bag filled with spiders and centipedes. Each of her tormentors has a turn adding a new crawling thing to the bag.

Critically, the segment of this scene where she's coerced into the bag is cut. We don't see how she ended up in it and are left to wonder if she willingly acquiesced to her punishment or if she resisted at all (assuming she even could). This omission builds on the game’s dream logic; how in dreams we often find ourselves in awful situations without a sense of how we got there or what led up to it. It is an extremely unpleasant conclusion, and yet within the dream entirely understandable. We can relatively easily imagine being subjugated by people who wield power over us, even if that power is tenuously constructed.

Jennifer being tormented by The Red Crayon Aristocrats in Rule of Rose.

We eventually learn that the entirety of the game is built from fragments of memories, spurred on by the culminating abuse Jennifer suffered at the hands of her peers. Narratively, it is all a very bad dream, one who's seams plainly make themselves known. These revelations at the end cause almost no cognitive whiplash. Rather, we're left with an ending that reinforces the themes that have been compounding throughout, of how power is psychologically enforced and how the trauma of having our agency stripped from us reshapes how we see the world.

There's a quiet moment at the end of Silent Hill which emphasizes similar themes of traumatic repression emerging through nightmares. Harry, after trudging through twisting iron and flesh hallways finds himself in a room. It's a simulacrum of his lost daughter's room, behind a sturdy locked door like one you'd find in a prison. Inconsistencies in space are not uncommon throughout the game but this feels different somehow. It's meticulously detailed, the game's intricate texture work on full display to highlight the nuances of light, shadow, and the occasional non-rusted color. It's familiar, somber, and wrong. It's an image that has stuck with me ever since I first played Silent Hill many years ago.

Alessa’s Room from Silent Hill

It's relatively easy to create monsters that horrify and unnerve, more difficult to create ones that get under your skin and linger, and harder still to effectively use unreality and uncanniness to build worlds that work like nightmares. Rule of Rose and Silent Hill demonstrate the power of this mode of horror. It’s stressful, compelling, and feels dire in ways that other modes do not. It picks you apart and leaves you feeling empty, exhausted, and truly powerless for when the monsters finally come.

Author’s note: I want to sincerely thank (and credit) my friend J Lynn for research assistance around Rule of Rose. This piece would have been far less possible without their help.

Hyacinth Nil (they/them) makes monsters. You can find them casting rituals to near-forgotten gods in the middle of the woods, playing apocalyptic dance music in an out-of-the-way warehouse, or in the desiccated husk of twitter at @Synodai. Most of their work lives on itch and Bandcamp.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it with a friend. If you'd like to help keep the lights on you can support the site on Ko-Fi.