Ronin Is Better When It's Not Itself

Ronin is not Gunpoint. These words pop up along the bottom of the screen within moments of pressing start, but even had Ronin not gone to the trouble of explicitly informing me, it would be rather a stretch to say it bares much of any similarity to Tom Francis’ stealth platformer save perhaps a passing graphical resemblance. And yet it seems that the one least convinced is Ronin itself, an insecurity that creates an experience that seems to exists primarily for the sake of proving what it’s not.

When the dance breaks so does everything else.

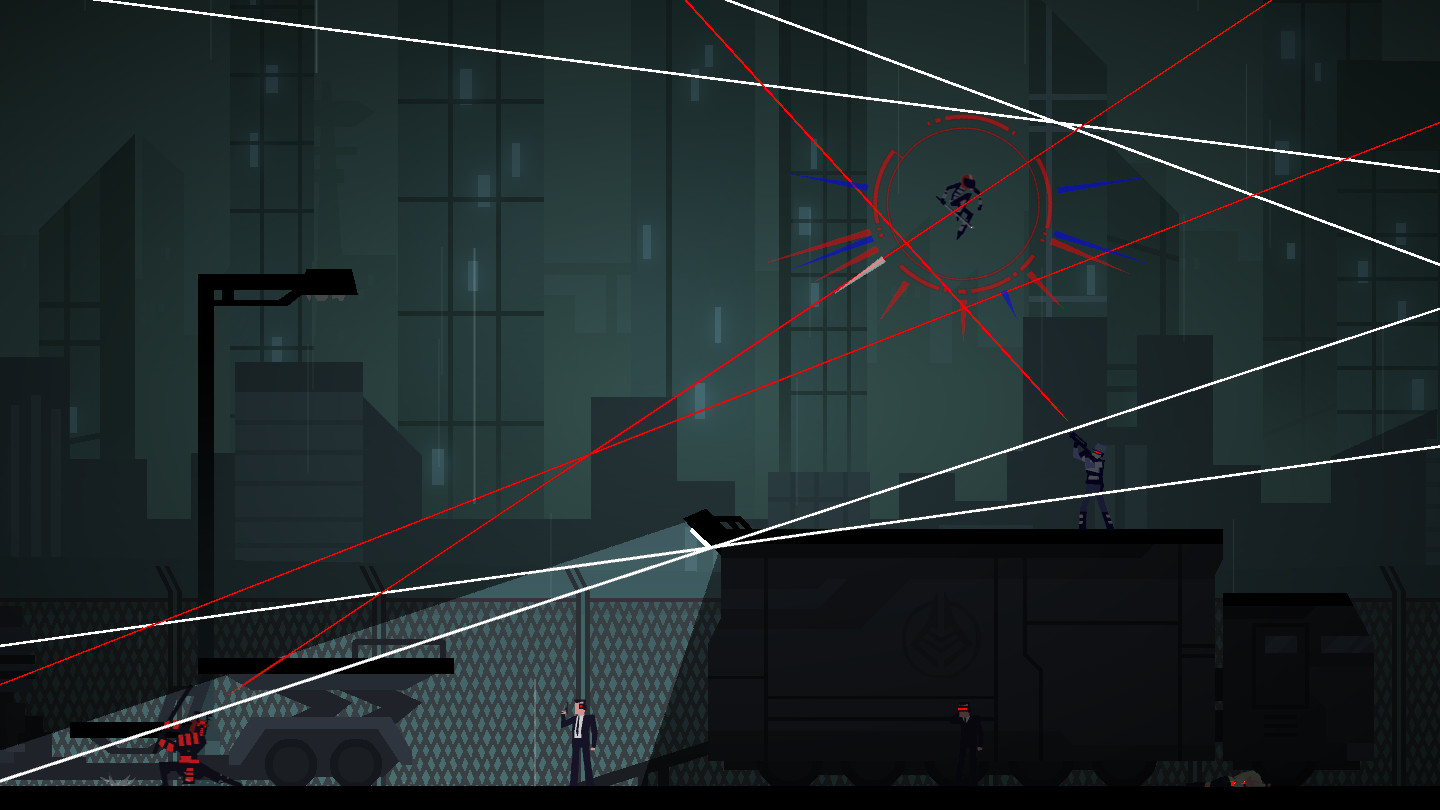

Ronin’s hook can be thought of as akin to choreographing a fight scene. Ronin’s predominant distinguishing feature is a turn based combat system that initiates whenever an enemy spots you, freezing time and allowing you one move before the enemy reacts. How this looks in practice is something like a dance between your character and the laser sights of your enemy’s gun. Jump, shoot, jump, stun, kill, repeat. The momentum of Ronin’s combat creates a very rhythmic, almost Zen like consistency that, when everyone is dancing as one, causes each successful kill to feel like the climax to a well-orchestrated plan. When the dance breaks, however, so does everything else.

For as compelling as the driving idea behind Ronin is, it never develops into anything more than an idea. Ronin treats its combat system as something inherently rewarding, but then inserts it into a game that feels designed around avoiding combat for as long as you can. Sure, Ronin will tell you, again, and again, that it is not a stealth game. But when so much about Ronin’s level design and means of measuring success are grounded in a stealthy play style, it is hard not to feel as if the game is sending mixed messages. Getting into a fight in Ronin should see the game at its most engaging, and yet it always feels like you’ve made a mistake.

Because of how limited your movement becomes once you engage with an enemy, picking enemies off from the shadows is consistently more successful and satisfying. And this is a problem, because aside from its combat system, Ronin is essentially a blank slate that fizzles out within the first three levels. Ronin feels like a demo that has self-replicated itself to be the length of a full game, increasing in difficulty, but only on account of upping the number of guards and the awkwardness of the areas you fight them in. Its design feels claustrophobic and stretched, allowing too little room for expansion but needing to fill space all the same.

Ronin’s problem is that it has built itself in such a way as to be constantly justifying its quirks. The combat system becomes needed only because everything else in the game is working to force you to use it, often in ways that are neither enjoyable nor interesting. And it’s because Ronin only really has one idea. It’s a cool idea, but its implementation is so simple that Ronin has to work extra hard to convince you of its worth. And I’m not sure that it actually succeeds at that.

Ronin spends a tremendous amount of time building a game to accommodate its combat system, but the same cannot be said of actually developing said combat system into one that can support an entire game. The more I attempted to work with Ronin, the more it seemed to fall apart, and I’d find myself dead by an enemy I had expected to dodge, or clipping along the edge of a wall and missing my jump. Ronin is far too precise to allow any room for error, but it is also exasperatingly clumsy and inconsistent on a basic technical level.

Real-time movement is janky and unintuitive, providing you with almost no means of movement that doesn’t involve spectacular but utterly impractical leaps across levels too small to need them. Ronin’s jumping obsession is moderately more usable in combat, but far more frustrating as well, given it becomes your sole means of movement, as if you were suddenly playing as a sociopathic frog. Far and away the most frustrating piece of Ronin’s half-baked game design pie though is in how it displays the various attacks and moves you can perform.

Because everything in Ronin is contextual, the inputs for the actions you can perform at any given moment are constantly changing. This isn’t an enormous problem in combat as you have time to look around and figure out which god-forsaken button a move has been remapped to, but in real-time situations I often found myself accidentally executing people when all I intended to do was go up the stairs. It is a small qualm on paper, but during Ronin’s later levels it is pure agony that continually forced me to restart at checkpoints that seemed to place themselves at random (or not at all).

Final Word

I will give Ronin one thing: it managed to both sell me on an idea and subsequently cause me to hope I never see it used like this again in a matter of hours. When its combat system works it is something all its own that rewards timing and spatial awareness. The majority of the time however it feels like a system in its infancy, one that continually repeats the same scenarios and becomes a little less compelling and a little more frustrating each time. Eventually, it begins to feel as if the game would have been better without the system at all.

I’m not really sure Ronin is concerned though; it just doesn’t want to be Gunpoint.