Lifeline - Review

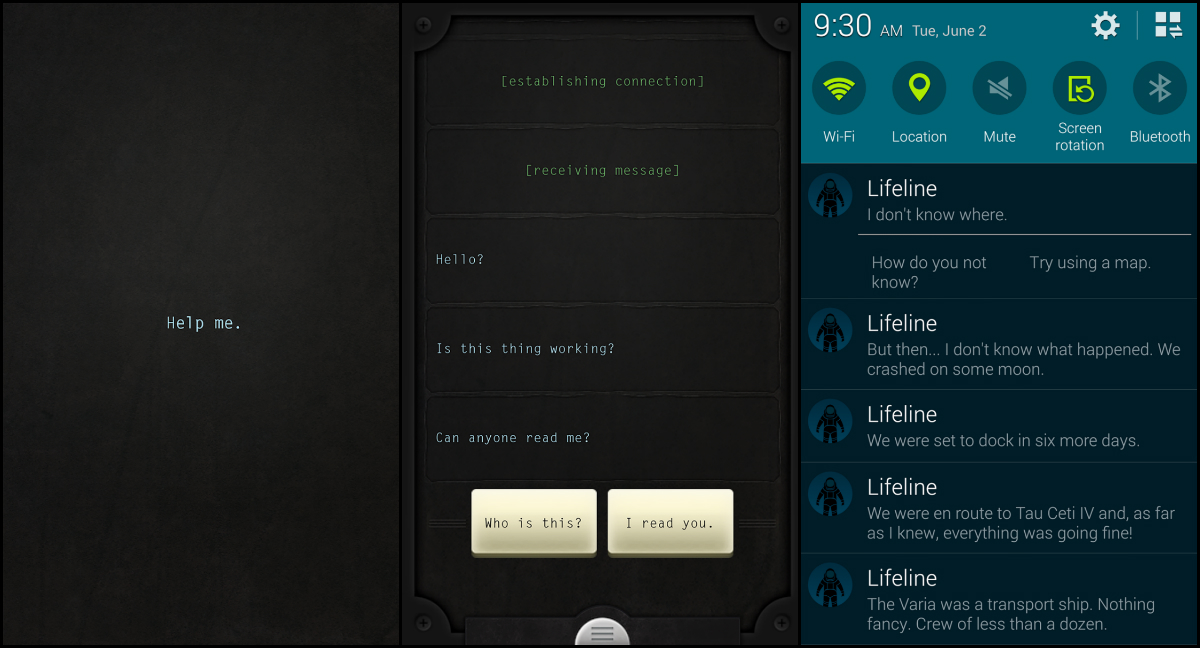

When is the last time you checked your phone? It doesn’t matter what for – a text, a Facebook comment, some stray likes on your heavily doctored Instagram pics – if you’re like me and the rest of modern technologically developed society, the answer is probably between five minutes ago to somewhere in the middle of reading this sentence. The act of pulling out your smartphone for no particular reason has become habitual to many, to the point where I’ll often find myself unlocking my phone without even realizing I’d taken it out of my pocket. There is an argument to be made for this being but the first part in a collective downfall of face-to-face communication, and for the ways in which being constantly connected to everyone and everything all the time is rewiring our brains for the worse, but while that is all well and good Lifeline has taken a different tactic: how can waiting for notifications be turned into a game? To be fair to the undervalued and now effectively extinct choose-your-own-adventure books of the 80’s and 90’s, Lifeline doesn’t posit a revolutionary change in storytelling mechanics. What it does it take an old idea and modernize it in a way that is so ingenious and perfectly suited to the platform it exists on that it has almost certainly been done before, but like so many visionary mobile games was likely lost under a torrent of exploiting F2P derivatives and whatever apps people are currently using to sext each other. Lifeline, in practical terms, is a texting adventure, where in you send messages (read: story decisions) to an astronaut whose ship has crash landed and is now relying on you to guide them to safety (why exactly they can only contact you is, as far as I was able to discover, never exactly explained). Think Andy Weir’s The Martian with fewer ties to reality and really good cell reception.

The twist is that Lifeline makes you wait. It sounds so basic on paper, but the process of sending a message and then waiting for your astronaut text-pal, Taylor, to carry it out and report back creates a sense of continuity and urgency through the mere act of most everything being carried out in real time (if Taylor says she’s an hour away from a peak, for example, you can bet you won’t be hearing from her again until that hour is up). In any other style of game or on another platform this would be obnoxiously tedious, but as a text-based narrative experience in the palm of your hand it feels not only natural but expected. Lifeline segments and rations itself in such a way as to be perfect for when I only had long enough to pull out my phone and scroll through messages, and by nature of being essentially a collection of very bizarre text messages itself naturally found its way into my typical notification checking routine. The design, as a concept, is almost perfect and I could see myself enjoying many more stories delivered like this in the future.

The problem is the story itself, which I guess when you’re discussing a narrative driven experience is akin to admiring the plate your food is served on as you struggle to actually stomach it. Lifeline’s biggest issue is the anecdotal nature of its storytelling structure, with each choice more or less embodying a small arc in Taylor’s story which is then thrown to the wayside in favor of something new and ostensibly exciting. Except when there are no established stakes (nor any penalties for failing to the point of death; you simply rewind and try again) it becomes increasingly hard to care about what it is Taylor is getting up to at 3AM. The Martian was very similar in this case, to return to a previous comparison, but where it excelled was in using hard science to explain impossible events, and in conjunction utilized an abundance of humor to developed its own marooned astronaut into an enjoyable character.

Lifeline does none of this, especially when it comes to explaining the increasingly bizarre and miraculous happenings of its sole character. Early on there is a moment in which Taylor asks you to read up on radiation poisoning so as to advise her on the safety of sleeping next to a generator, but after this point any pretense of factuality is thrown out the window along with most of your purpose for being there. Lifeline presents an absurd number of crazy ideas in attempts to make every choice seem paramount, but these only lead to more loose ends and increasingly limited information as to what choice you ought to make or why you are making it in the first place, concluding by pulling the metaphorical rug out from under you as it lets you know that those answers aren’t ever coming.

By placing nearly all of Taylor’s personal agency in your own hands, Lifeline also fails to create a character that comes across as anything resembling an actual human being. Taylor is sarcastic and occasionally witty, but her disposition is effected so entirely by what you tell her to do that it’s hard not to feel like you’re listening to your own voice being repeated back at you.

Lifeline’s narrative, overall, is a toss, but it lost me completely when it abandoned the one thing that makes it unique for the sake of a plot that barely exists. During the closing chapter of Taylor’s journey (which can encompass as much or little text as you allow her, depending on when you explicitly decide to let go of her hand), Lifeline stops caring about literal timeframes and begins to unravel events immediately following the other with no care as to the amount of time that is supposed to separate them. This is awful from a narrative consistency standpoint, but also from the time it begins to demand of the player. At times I became stuck in continual back to back walls of text which took upward of 30 minutes to complete. For having previously been so perfectly suited for mobile devices, Lifeline manages to diverge from every aspect of its intelligent design for reasons which retroactively hurt much of the experience as a whole.

Final Word

Lifeline is such a great template that I almost feel compelled to recommend it solely to show off the genius of its interface and delivery system. But once you dig into the game behind that UI it becomes a lot less engaging, and after a point I was almost mad that such a brilliant idea was being wasted on such a dire plot. Having the developers then abandon their own concepts later on is almost poetic in symbolically leaving them for better hands to wield. I have no doubt that given the relative success of Lifeline we will be seeing so, so many more games made in the same vein (mobile games are nothing if not good at capitalizing on a smart idea when they see one). My only fear is if they’ll make the same mistakes.