The Utopia of Murder: History in Anthology of the Killer

In an idyllic suburb, BB strolls through a pumpkin harvest festival. In place of jack-o’-lanterns, human gore is heaped on tabletop displays. Mutilated corpses nag BB to marry the corporate-approved Greg from High School while a woman’s severed head likens pumpkins to “corpses squeezed from shallow graves, as if the earth were too choked with flesh for further entry and the living were consigned to a narrowing circle within the legions of the dead, the numberless murdered of the history of the world.”

BB replies, “I get it, already!! Greg from High School!! Jesus!!”

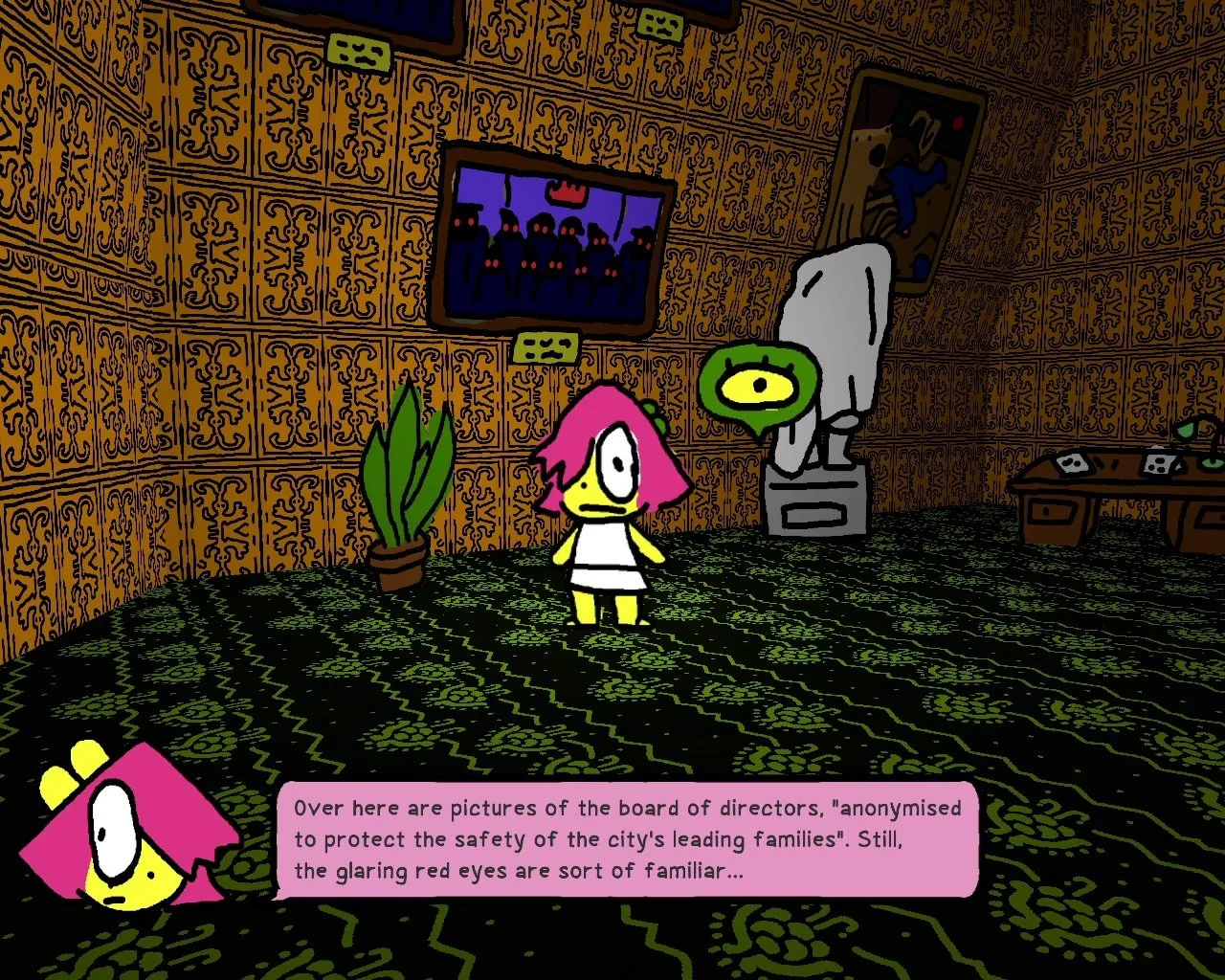

This scene occurs in “Heart of the Killer.” It is the eighth installment of Anthology of the Killer, a series of comedy-horror cartoon adventure games released from 2020 to 2024 by Space Funeral (2003) creator Stephen Gillmurphy. The player controls BB, a college student in XX City who reports on mysteries in her Strange Town zine, wandering through environments dense with scripted dialogue (even the chase scenes stay wordy). Invariably, BB discovers that another aspect of the city’s culture and civil society has been corrupted into an irrational murder conspiracy under the influence of a bird-headed arsonist known only as the Killer.

Though XX City is full of sinister knife-brandishing villains, only the Killer is spared mockery and pratfalls, looming alone as unvarnished horror. However, it is usually remote from the action. In “Heart of the Killer,” for example, the Killer never appears, but nonetheless the data the antagonists collect about sexual death fantasies is data about the Killer. It is not only a physical bird-monster but also an abstract force rendering other people its heart, its hands, its eyes, and other organs suggested in the episode titles. But what is the Killer?

Literally, the Killer turns out to be a prototype drinky bird automaton. Its official bio in the bonus materials states it is “possessed by an evil metaphor for history.” But this raises the question of what this metaphor means.

History is the series’ thematic axis. The second episode, “Hands of the Killer,” features BB introducing the history of XX City as transformations of an increasingly incomprehensible economy. “There was an Industrial period, a Retail period, a Service period, et cetera, until gradually the things it manufactured became too abstract and indecipherable to easily be summarized in any way.” Later, a college of the titular Hands of the Killer—under the tutelage of the Killer’s self-appointed acolyte Dr. Zoo—abduct BB for their hands-on murder labs, during which they give a more macabre perspective: history is a process of murder.

“Creating history is the duty of all murderers and in the tools they hack with we see the reflection of a new age that is to come. To perfect murder we must create a new universe devoted exclusively towards that purpose. We must also consider the possibility that we live in it already.”

On social media, Gillmurphy has pitched the Anthology as “Courage the Cowardly Dog meets the Angel of History,” referencing the ninth thesis of Walter Benjamin’s 1940 text “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” I will quote the version published by Schocken Books in Illuminations (1968), translated by Harry Zohn.

“Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage,” Benjamin writes, each explosion hurtling the angel backward too quickly for him to turn and see what happens next or to stop and “make whole what has been smashed” (257–258). The Killer is not Benjamin’s compassionate angel, but the explosions of murder that depopulate XX City demonstrate this history-as-catastrophe image.

History is replete with massacre, torture, and widespread cruelty, and history is far from over. “Voice of the Killer” introduces how normalized mass death is in XX City. Seeing a news report about thousands dead, BB says, “Same as always.” Considering the wars of aggression and continuing genocides of the twenty-first century alone, this banalization of atrocity is not an exaggeration. In “Blood of the Killer,” the patriotic Concerned Citizen describes his experience reading a zine that, apparently, gives a frank account of his country’s history. He froths with rage to find not the mythologized civic religion he was taught about the past but “a bad dream and a horror story in which all the names and faces [he] reveres from books and statues reappear instead as torturers and killers as toadies and functionaries of a charnel house … the beautiful history [he] adores and worships has been replaced by a lake of blood that has no bottom.” His gory efforts to deny this history cause him to join his forebearers as another functionary of a charnel house.

Like the Concerned Citizen, many deny, downplay, or even justify the horrors committed by names and faces from books and statues. History is made by murderers: Qin Shihuang, Julius Caesar, Christopher Columbus, Napoleon. Dr. Zoo calls classical sculptures “brilliant monuments, to kill people in the shadow of.” In the seventh thesis, Benjamin urges a view of traditional historical narratives as tacitly siding against the oppressed. The quote has become almost cliché:

“[T]he spoils [of the conquered] are carried along in the procession [of history]. They are called cultural treasures, and a historical materialist views them with cautious detachment. For without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. … There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism” (256).

The Anthology foregrounds history as horror, “[a]ll those squashed peasant revolts, interminable centuries of torture, beheadings,” a parade of murderers more extreme and gratuitous than the slasher villains who hound BB. As in the Concerned Citizen’s ramblings, Gillmurphy repeatedly likens history to oceans, rivers, or waves of blood, the drink for the drinky-bird Killer. An avatar of the Killer promises that one day “we will…be at the end of the calendar, and the streets shall be red with the blood of the calendar.” The end of history is less Dr. Zoo’s “utopia of murder” and more a final apocalyptic slaughter.

Bosso, a director at the Immersive Theater, is a Hand of the Killer who wields power through her access to the City Owners, a caste of blue bloods who “like prisons, mirrors, [and] violent death.” For her, history has become safely remote, a sprawling nightmare play straddling reality, kept up to amuse the Owners at a terrible cost of life (just not hers). Given the Hands’ widespread influence and that the Anthology frames each episode as a show in the theater, the whole series might be read as Bosso’s skewed theatrical take on history. But like the semi-fictional Count Masko she condemns to death in “Eyes of the Killer,” Bosso fails to recognize that her power is historically contingent, not a given. Never really controlling the reactionary forces she empowers, Bosso instead dies horribly in explosions of violence she assumed were part of her theater.

In a postmortem of the Anthology, Gillmurphy suggests a perspective in which apparent masters of history like Bosso, Cool Policeman (that is his name), and the City Owners “are not those who have dominated the world through their own strength and cunning but those who have allowed themselves to be remade completely in the image of forces they neither control nor understand.” In the Anthology, what propels history is not a dialectical progress, such as Hegel’s World-Spirit, but forces of totalizing violence neither controlled nor understood. These forces are the Killer, history as a serial killer.

Utilizing art, religion, philosophy, study, civics, and violence, characters try and inevitably fail to escape, understand, cope with, and control history. Many become murderers, symbolized by masks and red eyes. Some attempt to join forces with the Killer itself, but instead it kills them, their homes or offices burnt down.

In the final episode, “Face of the Killer,” although she is too late to save XX City or (apparently) her friends, BB defeats the Killer. Its body falls apart and the colors of the world invert, creating a literal negative of the former historical epoch. But BB is outraged that this is all thousands of deaths have purchased: “you remade the world and the only thing you wanted to change about it was the COLOUR SCHEME?” No less than Dr. Zoo chides her, “Look, it’s not good to be TOO critical.” The world might have already been his utopia of murder.

The other changes are trivial. The slasher villains who ran XX City are replaced with similar slasher villains, such as Strangleman, a different Bosso, and Tsar Nicholas II. Nonetheless hoping that the worst of history is over, BB fails to notice the new era’s Killer leering behind her, no longer avian in shape, knives already bloodied. Outside the Immersive Theater, where it seems to be helping the police perpetuate the endless massacre, this new Killer implies the process is cyclical, telling the player, “the next time I die I’ll come back as a bird.” In this history, the only transformation is the particular shape the Killer assumes. The change appears dialectical, but there is no genuine antithesis.

In the Anthology, BB’s confusion and frequent passivity offer no positive alternative to this “world of perpetual mass death.” But it is notable that the Killer does not arise by natural law. People create it. The Concerned Citizen never accepts that his bourgeois father built the Killer, matching his factories’ industrial runoff that stained River Town’s water red, a metaphorical river of blood, with a literal river of blood. The new era’s Killer is also a constructed product, cosplay of the Hands’ horror films and shaped by an unaware BB. If each Killer is manufactured, some other history might be created instead.

After the disappointment of the color negative, BB, a chronicler of history, closes her final zine wandering suburbia. Donning their murderer masks, the affluent locals are already sizing her up as their next victim. BB gazes longingly through the gaps in one of the fences around her and writes that alternate futures might exist, but these archetypal symbols of private property deny access to them.

“The back yards are fenced away, but at bits you can look through and glimpse some new place, open and uncertain, in the chance intersection of a wall, a roof, a vacant lot[.] As though still folded up inside the world there was a different kind of negative[.]”

The ubiquitous invitation to laugh at the bottomless lake of blood also means the conclusion can’t really be despair. This straight-faced analysis might obscure that Gillmurphy’s writing is hilarious: “TAMMY was granted a vision of the new economy. Political scientists refer to this as, ‘ECONOMY 2.’” In the fourth thesis on history, Benjamin writes about the “refined and spiritual things” that oppressed people already possess before winning their struggle. Humor is one of these refined and spiritual values that “constantly call in question every victory, past and present, of the rulers” (255). BB finds her own ways of coping: “Weary of my travels [… I] spent the day playing videogames, instead.”

WD (he/him) is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin. You can read more of his writing on his personal site, Medium, and Tumblr, and watch his videos on Youtube. You can follow him on Bluesky @mackerelphones.bsky.social, and support him on Ko-Fi.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it with a friend. If you'd like to help keep the lights on you can support KRITIQAL on Ko-Fi.