And there will be no one to cross the Rubicon

In 1871, as the forces of the National Guard push the French Republic out of the Parisian borders, the Paris Commune is established, marking the first anti-capitalist revolution in human history. While short lived, the discussion held by the Central Committee of the Commune on the budding rule of the working class goes on to influence the budding European socialist movements which follow. In the wake of this, Karl Marx’s tectonic Capital (1867-1894) is written, equipping the workers’ movements of the world with tools to understand the exact system by which they are exploited. The bloody conditions of capitalism become more and more acute until, in October 1917, the Russian Bolshevik party ousts the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries from the Congress of Soviets, returning over 400 thousand acres of land to the peasantry and collectively freeing the people of an annual rent amounting to 500 million rubles (not adjusted for inflation). These same Bolsheviks later assist in training the People’s Liberation Party of China, who, despite a deficit of over a million troops, defeat the bourgeois Kuomintang and establish the People’s Republic of China.

Revolution, while frequently assembled as the work of solitary leaders, is only brought about by the masses. Theorists and political leaders of these anti-capitalist revolutions may take up a role of making the complicated and parasitic organization of the world clearer, or handle logistical and organizational duties after a long time of organizing among the people, but in the scope of society one person can change nothing substantial. Not two nor three nor ten nor fifty. To change the world, you need the world and its masses to come along with you. The irrational brutality of the ruling order and the power held within the labor-power of the masses must be made clear and unmistakable for them to take arms.

A slim mint green mech suspended in an appropriately sized garage. It has crimson undertones and its chest piece has a decal which reads “Wish”.

On Rubicon, the terrestrial body of Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon (From Software, 2023), it seems like no one lives, works, or struggles. The latest entry in From Software’s once forgotten franchise mostly follows suit of its predecessors. A set of corporations vies for control of society’s most important resources while a dominant but ephemeral-feeling government body intervenes only when absolutely necessary. Down in the trenches, our lowly freelancing pilot (called a Raven by name or by paramilitary position) takes missions for all sides, killing strikers or enemy units as is convenient. She steers her mech – the titular armored core – as best she can, paying for every bullet down to the penny. A player glimpses short calls and additional information about the world between new missions until they eventually get into trouble with one or all of the factions for being too effective.

In a turn from the franchise’s often cynical and futile presentation of economic conflict, Fires of Rubicon tries to ignite a spark of revolution while only giving us what happens around one soldier’s machine of destruction. The upheaval of society and the tides of revolution are decided by the masses and not great individuals. To change society, the actual way we relate to one another – from how we get our necessities to where we physically meet – must materially change. From the cockpit, you can only see execution targets and your dull reflection against the instruments.

As a kind of drama, mecha best operates to show the failures of the imperialist organization of the world along with all its horrors. You can look to the original Mobile Suit Gundam (Yoshiyuki Tomino, 1979) cosmology, which hands us the now genre codified petulant teen pilot who’s made to suffer the conditions of war before becoming an adult twisted into a figure of an imperialist United Earth Federation, all the while keeping newly enlisted child soldiers in line. Or Armored Troopers Votoms (Ryōsuke Takahashi, 1983), which shows us an adept at war being constantly rejected by society and flung into combat zones, lacking the social insight or connections to remedy his lot. Soldiers and mercenaries are powerful actors with strong wills, who, despite it all, cannot change the tides of war let alone see past themselves. Orders are obeyed and combatants with just as much love, anger and sorrow as our sympathetic pilot get cut down in an instant, never to return. Meanwhile, some faceless bigwig higher up gets a promotion and the capitalists reaping the profit of the war line their pockets.

The format of Armored Core has historically been designed for this method of storytelling. The games open on an introductory mission before submitting you to a singular and unchanging loop. Our Raven enters the garage where they maintain our death machine and receive orders from whoever is paying. You can select a briefing on where to go and who to kill before setting off, as long as the price is right. Our armored core is dropped into the fray where you endure the blistering and complicated movement of our custom tool of destruction. Simply keeping an enemy in your sights and moving appropriately, let alone landing a shot or staying in one piece, keeps every moment and individual mission spicy. When all is completed, you return to the garage to front the bill for excess destruction, ammunition, and repairs, ready for more work at a later date.

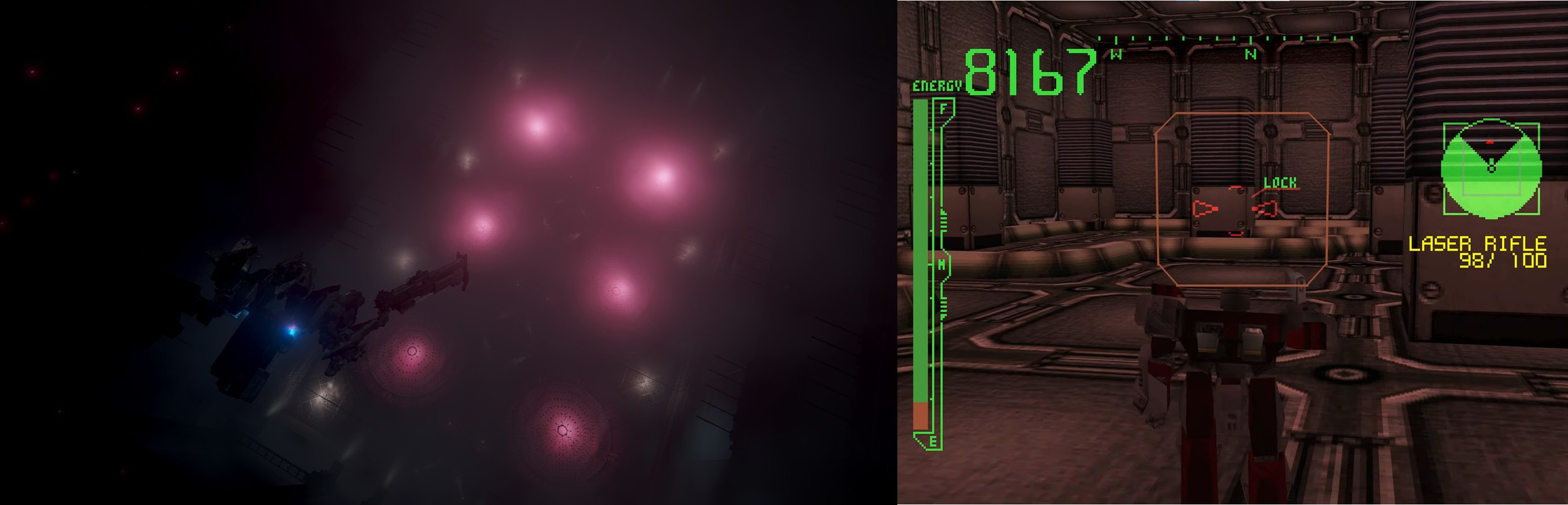

A side-by-side of a mech descending towards a set of glowing lights in an open-air industrial plant from Armored Core 6 next to a grounded mech advancing in a closed plant of electrical pylons with dingy lighting in the original Armored Core.

The Raven does not go into the world for anything other than killing on the company dime, or if they do, we cannot see it. The supposed freedom and superiority of the freelancer is stripped bare for what it is: a wage laborer with just a bit less supervision and more money than the striking factory workers you just killed. A pilot only deploys with orders. There is no way in the system of the game to explore the world of your own will, to express the alleged autonomy a freelancing pilot should have. The world you see consists of only the bloodiest and most desolate workplaces of the world: production factories and battlefields.

Fires of Rubicon complicates this narrative method by the inclusion of two navigator characters who join you in the garage to curate jobs and advise you on what course of action to take mid-mission. One, Walter, is a man who has supervised the forced human experimentation conducted on you for the purpose of exploiting your piloting skills for his personal schemes. While he is frequently hands-off and aloof, it is clear that he is using you for a larger goal which goes unrevealed for most of the game. Following him is Ayre, a disembodied Rubiconian who seems to live through Coral particles, the spiritually imbued precious energy which the corporations of the planet feud over. Ayre saves our Raven when they’re almost killed in an outpouring of Coral by psychically linking to our pilot and machine. Walter cannot hear her voice but suspects her influence as she implores our pilot to consider this situation from all sides.

These two become the primary voices of the pilot, a standard cycle of the game culminating in you choosing whose will to follow towards diverging endings. Walter wishes to dispose of all the Coral energy to right the wrongs of humanity’s past, while Ayre wishes to forge a path towards a world where humanity can live harmoniously with Coral, now housing the spirits of lives lost in the decades long conflict. Each conclusion depicts the Raven making a decision which dramatically shifts the conditions of the world, causing the planetary government and the largest monopoly corporations to have their hold either completely sundered or dramatically weakened.

To develop the stakes of these choices Fires of Rubicon breaks some franchise conventions, creating space between the player and the pilot in odd places. Dramatic scenes occur outside of the view of Raven, engineered to clue the player in on who the scheming actors are and to curry sympathy for Walter, who would otherwise be just a man who has warped our body for war. These happen in the completely non-diegetic garage UI, visible to us but not our character, sharing more with the Apex Legends (Respawn Entertainment, 2019) lobby screen than a hypothetical garage management software.

A side-by-side of the garage UI, showing a mech hanging idle next to menu options in Armored Core IV, while a full screen software interface cycles in the original Armored Core.

Where other entries sought to alienate the player when they entered the mech, Fires of Rubicon leaves us to identify with the only persistent figure of the game, our armored core, and the constant address of the Raven. The opening of the game asks for a pilot name, but you’re only ever addressed by either your experimentation case number, 621, or Raven, a name stolen from a corpse in the introduction. In a previous iteration, where we follow the pilot sending and answering emails as a clerical element of freelancing, Raven and your callsign are a professional formality of privacy in a violent field of work; here, the Raven is deployed more like the earnest and general address of Hero in a Dragon Quest entry. You, your robot, is powerful. Embodying it is exciting. It is lush and thrilling to move in the world, to swing your omnipresent camera around your diorama of a garage to get cool pics of your guy.

Except it should fucking suck to be in this line of work! The franchise has half-turned away from being an interface driven simulator of freelancing for blood money and the personal managerial work that accompanies it, swinging hard into uncritical power fantasy. The shit hole world is still a shit hole but it is far too grand and metropolitan, lacking interior spaces where humans would potentially work. The general combatant is still dramatically weaker than whatever vehicle the player can mash together, but the long strings of horrible and monotonous work are jettisoned in favor of a curated chapter structure telling a clear three act story. Missions give you a target to destroy or defend but are often structured around grand looking locales with scaled-up and frequently non-human bosses, making every workday a little too epic. The game is still quite difficult, but where the control scheme of prior entries heightened the sense of engaging with a machine’s controls by obtusely mapping looking and moving to individual buttons per direction, the now standard-since-the-mid-2000s dual stick camera control scheme makes the mech fade into your hands. Weapons which are only fireable after cooldown timers make me feel more like I’m steering a League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009) character than an unwieldy war machine and further flattens any pointed sensory disconnect between me and my armored core.

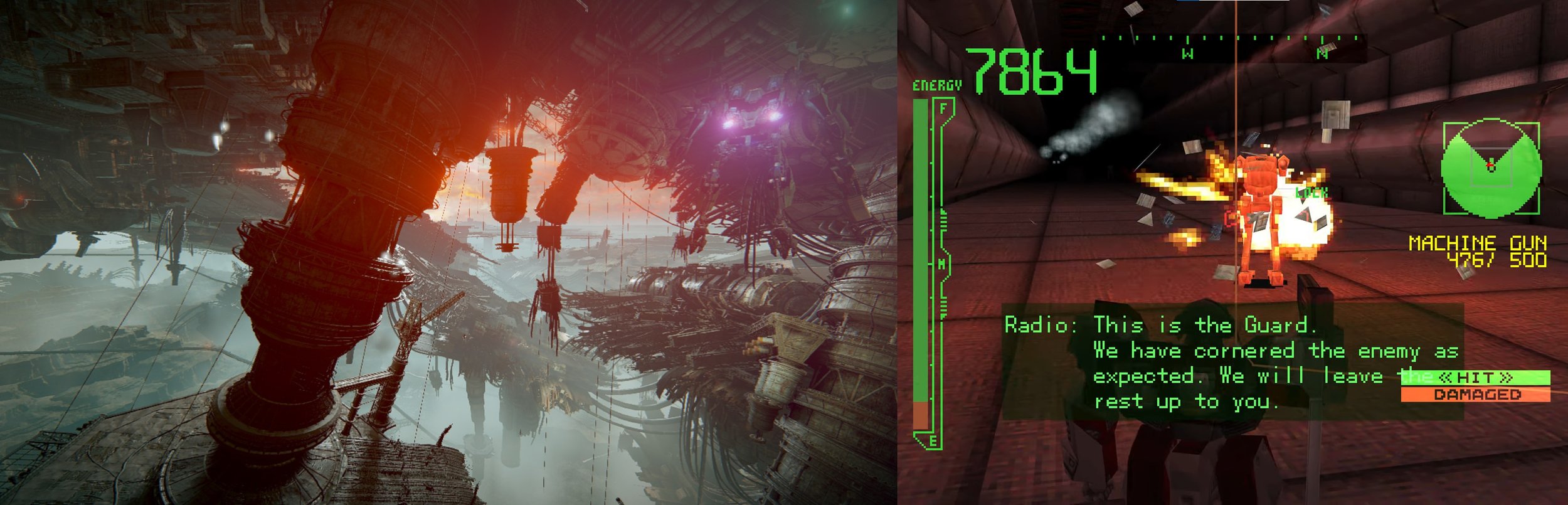

A side-by-side of a mech hovering over a multi-layered and confusing landscape of scrapped facilities in Armored Core 6 while a mech walks through a dim sewer, firing at an enemy in the original Armored Core.

Such a strong lack of the human element casts a shadow of the absurd over Fires of Rubicon. Much of the game’s moral compass making is propped up by favor gained with a wimpy and characterless liberation group and a general motivation to free the people from the tyranny of corporations and the government. Yet, people directly responsible for the global conflict constantly take the stage to speak in broad strokes. A many months long, costly factional war is skipped over in seconds as the game ramps up to its third act, making it clear how much the game wants its triumphant military fantasy without any of the pesky realities of the rank-and-file or general masses. The game never leaves off with a rosy epilogue – the Rubiconians, wherever they are, are not explicitly saved – but we’re certainly left with enough space to say that maybe you can change global modes of production by murdering petty middle-men of the ruling class as a one man wrecking ball.

Fires of Rubicon offers a lucious, bloodless, and spectacular piloting experience. It adds a prominent sense of drama to the franchise when it has often pushed away players by forcing them to make sense of a plot through the most ominous emails possible. It is a blast to zip around with what seems to be the most universally well received iteration of modern controls since the franchise broke up with the classic controls. While in your personal life it’s fine to say “well that was fun” and wash your hands of a game, the objective of criticism is to make clear what a work of art, media, or entertainment achieves and what parts of our society it reflects.

I am doubtful of the military mecha genre’s capabilities to tell anything other than cynical stories of social defeat despite military victories, and this game is a proponent of that doubt. I can envision a world where mecha is used for a broader ensemble, scratching at the sense of collective power expressed in something like The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966), but I don’t know if I can see Armored Core doing that. The complicated reality of two million People’s Liberation Party Troops overcoming 3.7 million Kuomintang or the sudden turn of the French Republic’s troops to favor the National Guard is too rich in organizational dilemma and too full of human expression to see from the cockpit.

Further Reading

Abidor, Mitchell. Communards: The Story of the Paris Commune of 1871, As Told By Those Who Fought for It. Marxists Internet Archive Publications, 2011.

Stalin, Joseph. History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course. OGIZ Gosizdat, 1938.

Kan-Chih, Ho. A History of the Modern Chinese Revolution (1919 - 1956). Foreign Languages Press Peking, 1959.

Axe Binondo (they/them) independently does writing, visual art, music, and game making as well as podcast cohosting here on KRITIQAL's Zero Context, all in no particular order. Check out everything they make here, see what they're posting on Twitter @wing_blade_, on Cohost @wingblade, and support them on Ko-Fi.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it with a friend. If you'd like to help keep the lights on you can support KRITIQAL on Ko-Fi.