You can’t prevent wildfires: A Firewatch Review

Life is cruel and unfair, but damn if it doesn’t look beautiful as it’s burning down around you. Firewatch is a game preoccupied with the messy, unpredictable, and indiscernible tragedy of life. Though its aesthetics and settings might lead to the perception of some natural focus - canyons and forests of the Wyoming wilderness forming a backdrop to elevate a narrative of environmental concerns, perhaps, or at least one in which the outdoors inform the game’s trajectory beyond mere blunt scenery - Firewatch is wholly absorbed in the interpersonal drama between its two main characters, Henry and Delilah.

Henry is a man running from his problems; Delilah has already gotten that far but still can’t put her own problems out of mind. Together they form what could be described as Firewatch’s soul; the humanity hidden beneath inconsistent world building and awkward mechanical conceits which holds the game together, if only insofar as people keep talking. For as tired and archetypical as its two troubled protagonists are, Firewatch is successful through its refusal to ever satisfy the player. Though it begins in a familiar place, Henry and Delilah’s story is never allowed to diverge onto the path you expect it, and most likely want it to take. Firewatch constantly dangles relief just outside of reach, situations and conversations building upon the uncertainty and anxiety of two people so completely lost in their lives looking for a way out, even if it means destroying themselves in the process.

This isn’t to say that Firewatch is grim, so much as it’s uncompromising. There is a delicate balance struck between wit and sobriety which allows Firewatch to be at once charmingly aloof and unpleasantly blunt. The only significant form of exposition comes by way of the radio conversations between Henry and Delilah, and a lot of care has been put into the way you as a third person are in both direct and subtle ways influencing and witnessing their relationship develop. Often you are afforded a personal choice as to the tone a conversation takes on, which by nature of being (if only slightly) player directed causes Henry and Delilah to feel like more dynamic characters. But it is also in what Firewatch doesn’t tell you that contributes to their authenticity, with days and sometimes weeks going by without your involvement, and scenes often fading to black before the entirety of a conversation can be told.

Again there is a willingness to frustrate the player for the sake of creating more compelling and autonomous characters, and while this could have fallen apart and left us with a game bereft of depth and cohesion it’s such a conscious and considered decision that it creates an experience that feels confident in its own ambiguity and discontent. Even up to the end after all questions are laid clean and revelations prove far less fantastical than the possibilities leading to them, Firewatch remains deliberately unsatisfying and sometimes even intensely frustrating. All to the point that the world Firewatch wishes to portray is inherently unfair and unexciting, and often the ways in which we try to find meaning within that framework are only for the sake of our own gratification and to satisfy the belief that there is a purpose to this all. Because ultimately Firewatch’s narrative is decidedly mundane even in its least ordinary moments, only taking on a larger significance in the presence of its two characters who are so very distressed and by nature feel so relatable and well realized in their attempts to make sense of the impossible.

There were several notable moments where I expected Firewatch to branch off onto a larger potentially more exciting path, but I find a significant appreciation for how confined and unfulfilling its plot actually is. There is the immediate impulse to feel outraged at Firewatch’s audacity to so completely reject the player, but beyond that there is something to be said for examining our own need to feel justified by the media we consume, when maybe there is more to be said by never arriving at the happy or thrilling conclusion we expect. Maybe it is worth considering that the inconclusive and ordinary can meaningful in its own way solely through the people we share those moments with.

But for all its narrative unorthodoxy Firewatch is a far less cohesive game than it is a storytelling device. Firewatch is so careful in its exposition and dialogue that it’s bizarre and agonizing that none of that care has been put into considering the way in which the game’s world and its mechanical habits interact with one another. Firewatch plays like a string of narrative conveniences and diversions, introducing new mechanics and ways to use them in such transparent fashion as to shatter the illusion of being present in this world so much of the game is predicated upon reinforcing. Firewatch spends an inordinate amount of time reminding you of your characters body and the ways in which it collides with the natural world you need to navigate through, and yet your body is no less impervious and superlative than any given video game character. Firewatch wants you to watch your character scramble a rock wall, but also won’t deny you an endless sprint button so as to not trouble you with the need to spend any extraneous time walking through the landscape. It wants you to feel dazed as Henry slips down a slope, but worry not about dropping off that ledge, a perfect landing is always assured.

Actually playing Firewatch often feels like a chore.

These are small things in context, but when so much of Firewatch is attempting to break away from the conventions of traditional game design they stand out as inexplicable reminders that underneath the narrative this still a fairly ordinary and unexceptional game. And that realization causes the act of actually playing Firewatch to often feel like a chore; a simple but tedious and obligatory gesture done purely for the sake of narrative.

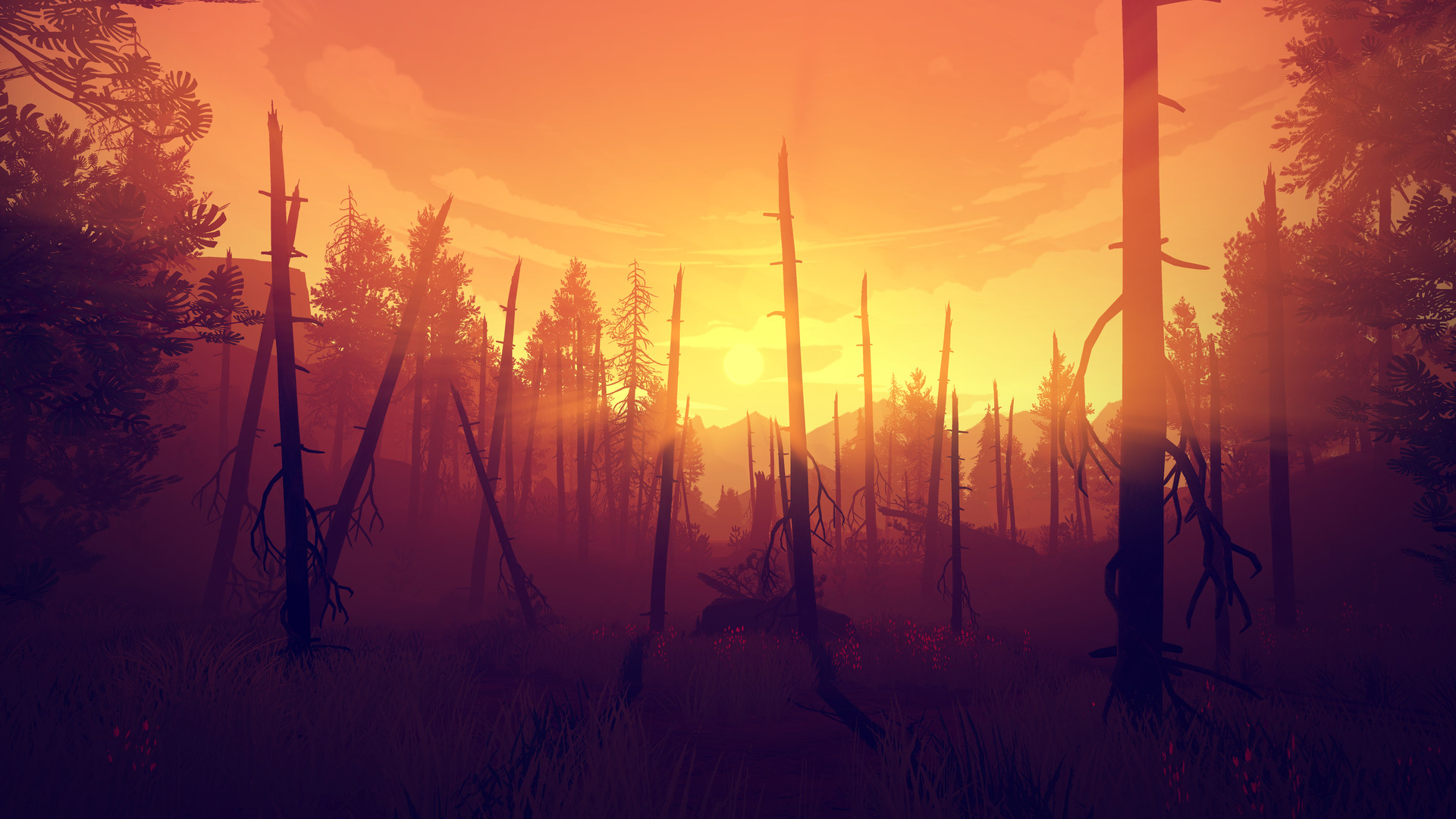

And if playing Firewatch is uninteresting to the degree I would simply rather not, what purpose then do the vast and beautiful landscapes serve beyond extensive gaps between story beats I’m forced to run through. When Firewatch neglects to make the act of actually playing it engaging in its own right, it creates no incentive or desire to spend any extra time within its world because everything outside of the story is deemed less important, a story which in turn could have just as easily been told in any number of settings further degrading the perceived value of exploring its world.

It isn’t even that this isn’t a world I would like to appreciate, as meandering about its trees and hills so perfectly captures the feeling of being lost within the wilderness that I wouldn’t feel opposed to merely trapesing through a nestle of trees for no other reason than to watch how the light breaks through them. Firewatch is exceptional in its artistic direction and each frame could be captured and displayed as a beautiful painting in its own right. But by creating a hierarchy of purpose between its gameplay and narrative Firewatch causes time spent outside of its story to feel wasted, or at the very least as if you are holding the game up from showing you what it really wants to. It wasn’t long before I lost most of my desire to just take in the world I was walking through, as I felt constantly funneled from one story beat to the next and couldn’t shake the feeling of idleness anytime I’d stop to admire a particularly lovely vista. Firewatch didn’t need to incentivize exploration, but it failed in making it seem a worthwhile undertaking and it’s easily the game’s biggest folly.

Final Word

Firewatch’s strength lies in its simplicity and humanity. Its uncompromising narrative is often deeply frustrating, but in crafting a world so completely mundane and ordinary populated with messy problems without easy answer, it manages to tap into a specific segment of the human experience so rarely explored in games. It’s unfortunate its mechanical foundation is so much less unexpected and disrupting, coming close at times to taking the rest of the game down with it as Firewatch’s two conflicting halves struggle to find any sort of balance. In the end its problems aren't all that different from the wildfire that springs up early on in the game. They’re always there and keep getting bigger, but we just ignore them and hope they’ll be dealt with before the whole place goes up in flames.