Absolute Drift goes round and round and round and round

Drifting has always existed as a sort of accessory sport to traditional racing. Flashy and dangerous, drifting — the act of taking a corner so as to lose control of the back wheels and cause the car to turn sideways — prizes style and precision over speed and vehicular power. Though organized events such as the US’s Formula D series exist they are still searching for a large audience, and outside of Japan drifting remains largely a novelty, something to spice up action movies and arcade racers but rarely thought of as a legitimate sport itself.

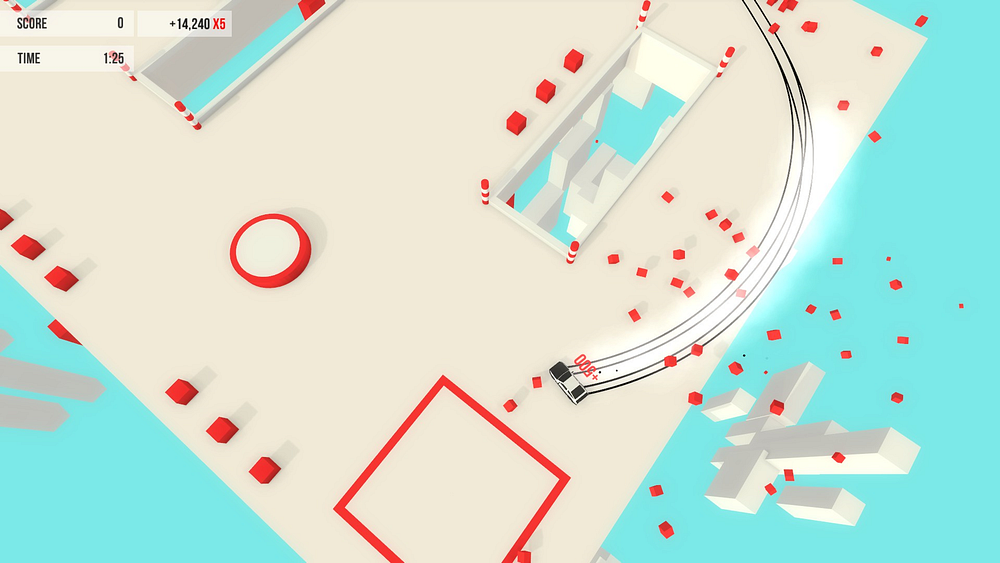

Absolute Drift (2015) feels in large part an attempt to move away from drifting as spectacle, giving you a car and a road and letting you figure out the rest. The presentation is stripped down to blunt polygonal buildings and red highlights to tell you where to go, with your car itself a nondescript toy-sized vehicle only visible by its bright paint job and lengthy tire tracks.

When placed next to the gleeful excess of Need for Speed or the cartoony impossibility of Mario Kart, Absolute Drift singular focus is clean and consolidated. Drifting is the literal name of the game, so drift away to your heart’s content, careening through rectangular roads that only further emphasize the exacting grace of your curve.

In a 1995 interview on Jeremy Clarkson’s Motorworld, drifting progenitor and legend Keiichi “Drift King” Tsuchiya says that one of the reasons he began drifting was to entertain the crowd during racing events. It was almost always assured he would win, so drifting became a way to put excitement back into a race where the outcome was no longer the reason to watch. This ideology is a key component to drifting’s popularity in media and as a spectator event. Watching cars go fast is fun, but watching cars go fast and take turns in ways that seem to defy the laws of physics is exhilarating.

One of Absolute Drift’s earliest contradictions is in its reliance on traditional events and score attacks as means of creating a sense of progression. Absolute Drift’s prevailing methodology is that drifting is itself reward enough, and that the problem with the way drifting is used in other media is that it has become deluded by the obsessive adoration paid to it by movies like The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006). Drifting should be about the screech of your tires and the smoke of your skid marks, Absolute Drift seems to say as it positions drifting in an almost religious context (the game itself opens with a Shinto deity welcoming you into a sort of drift heaven).

And yet here the game is asking you to do a donut around this building, or jump your car over this gap. The problem with Absolute Drift’s attempt at drifting solidarity is not that it doesn’t stick to that goal, but that it never could. As Zach Kotzer writes for Kill Screen, “drifting is not an absolute; it is a means to an end.” Absolute Drift needs its leaderboards and its car stunts because drifting in isolation just isn’t that interesting. Just as Tsuchiya incorporated drifting into his racing to spice up his corners, racing games have utilized drifting for the similar purpose of making themselves more interesting to play and watch.

When you strip everything but drifting away from these games, sliding through corners begins to dull rather than excite. Absolute Drift may see drifting as an elevated form of racing, but there is a reason the sport has only ever garnered a niche audience. There are only so many ways you can drift the same turn before it starts to feel routine. This is a problem for games with far more robust handling systems than Absolute Drift can manage (your toy car feels like a boat cruising through a bowl of ice cream), which only exacerbates the problem as what is drifting but the precise understanding and control of a car’s grip and power.

Final Word

Absolute Drift’s devotion to a singular idea is compelling in its focus and clean production. Its sparse world is as easy on the eyes as the trance soundtrack is on the ears, and there is some fun to be had navigating these large sandboxes populated with fighter jets and Ferris Wheels. But that fun is akin to setting up a ramp and watching a Hot Wheels car fly down it, popping off the ground and begging you to do it again. Eventually you grow tired of this simple task and long for something more involving. But your toy is still just a Hot Wheels car, and this is still just a drifting game.