Games vs narrative and why it shouldn't have to be that way

It took a long time to get here, folks, but we seem to finally be entering a stage of video games being taken seriously as a medium for storytelling. That isn’t to say games haven’t been telling great stories for years (they have), but it no longer feels like an exception to the rule for a game to have a story worth experiencing, nor is it still considered taboo to criticize a game for a garbage narrative on the basis of games being somehow incapable of decent writing. After so many years of clichéd plots and shallow characters, we’re seeing games with important things to say, capable of inciting emotion and empathy from players; of being more than a conduit to deliver us from one gameplay scenario to the next. We still see a lot of the same stories we’ve been rolling our eyes at for decades, but they’re becoming less and less common as we raise our collective standards and demand better, because we know our games are capable of it.

All that said, one thing we’ve been very reluctant to discard is our way of thinking of gameplay and narrative as two separate entities, coexisting in our games but to be taken and judged on their own merits with little thought to how they fit together. Story is confined to cutscenes and dialogue boxes, instructed to feed us dialogue in between bits of gameplay as a sort of reprieve before we go back to doing whatever the game otherwise consists of. It’s perhaps because our methods of storytelling have been so primitive for so long that we’ve fallen into the habit of keeping various elements of games in their own boxes as if one doesn’t and shouldn’t influence the other.

But by doing so we’re both limiting games as storytelling devices, and discrediting the stories that our being told, often considering them last on the list of qualifications of what makes a game “good”. I’m not trying to say that cutscenes should go away or that you can’t tell a great story using the styles we’ve been lifting from other mediums (mostly film), but games are special in that they allow stories to be told in so many ways unique of other mediums, by way of player interaction and utilizing a game’s mechanics.

Perhaps the most popular way this has been done, especially recently with the likes of “Gone Home” and “Bioshock”, is through exploration and nonlinear world building. Allowing players to explore a location of their own volition, taking it in at their own pace as they peek into corners and inspect objects, creates a cohesiveness that’s only possible in a medium unrestrained by words or camera pans. It also lets stories be told in a way that gives them a natural context, such as in “Ether One” where each puzzle is used to provide a greater insight into the lives of characters and the world they inhabited. It allows writers to create elaborate backstories and environments without having to flood the player with tedious amounts of lore or hours of cutscenes, using the world itself to tell its story to as much an extent as the player wishes to seek out.

The danger here of course is that players will miss important plot details and become lost, which can sometimes create the impression that there isn’t a story at all. The ideal solution is to reinforce narrative with gameplay, which is where most games give up. It’s one thing to use a game’s world to help tell a story, but rather a lot harder to cohesively link gameplay and narrative together, both because they’re often created by different people operating independently and also because developers seem to rarely consider how gameplay and narrative can help each other if used in tandem. The result is a lot of games that seem to be saying one thing with their narrative, while their gameplay says something different, commonly referred to as ludonarrative dissonance.

It makes for games that continue to hold to the idea of games and narrative as opposing forces, often leading to stories that seem at the mercy of whatever gameplay convention they have to work with. It causes games like “Uncharted” to introduce bizarre supernatural elements, because hey, shooting zombies is cool! Or “Remember Me” to end with an arbitrary boss fight because that’s how video games have to end.

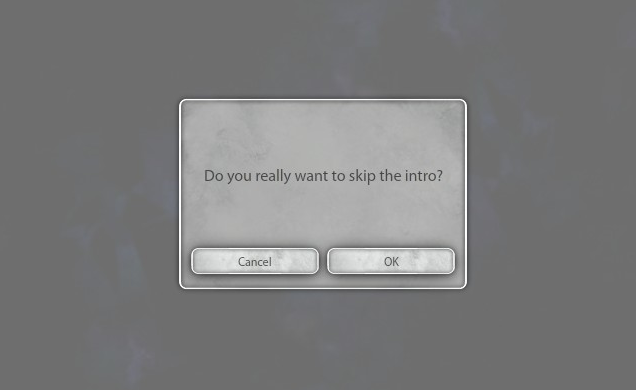

Or there are other, less obvious problems, the ones usually ignored because we’ve grown so used to them. Things like how characters can kill thousands of people and never feel the effects of performing mass homicide, or how you can begin an urgent quest and then spend hours grinding for experience points.

I get it, not everything needs to have logical consequences or follow real world rules. There can be games that are fun or engaging without needing to resolve everything they put forth. But if we are ever going to get out of the mindset of games being games and stories being stories, we need to start considering how the two affect each other and can be used to better both sides. Seeing games like “Brothers” move me to tears without a single line of dialogue show how intrinsically tying plot progression to player actions can be more powerful than any number of cutscenes ever could. The emergent stories created in the likes of “State of Decay” also highlight how sometimes it’s best to forgo a set narrative entirely, in favor of letting the players write their own using the gameplay hooks set in place.

I don’t expect cutscenes to go anywhere, nor should they, but if we are to ever start looking at gameplay and story as two inseparable parts of the same experience games in turn need to stop treating them as one. With so many games telling amazing stories, it’s unfair to continue to act as if they’re any less relevant to a game’s worth than how it plays, or that any game can or should attempt to tell any kind of story it wants. It’s important for developers to consider the game they’re making and how its gameplay and plot reflect on one another, and in turn players need to recognize that relationship instead of divorcing different parts of games from each other as if they’re different parts of a meal to be consumed individually.

Perhaps that asking a lot, but I think it needs to be stated if we ever want games to be appreciated in the same way film and literature is, but for their own merits, not the ones they’ve borrowed.